Coming October we celebrate the 40s anniversary of the Schleswig-Holstein Wadden Sea national park. At this occasion Thomas Krumenacker published as RiffReporter an interview with Karsten Reise, who for many years headed the Wadden Sea Station of the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research on Sylt – and played a key role in having the Wadden Sea declared a World Heritage Site. Our German readers may find the interview directly at RiffReporter.

——————

RiffReporter is a cooperative online magazine.

As an association of freelance authors, they stand for high-quality journalism and passionate research on the relevant issues of our time. RiffReporter is owned by its authors and supporters. I can only recommend to subscribe to their news of high value in respect to nature conservation.

This article is part of the project ‘Has the limit been exceeded? Significance, situation and future of the Wadden Sea World Heritage Site’, funded by the HERING Foundation for Nature and People.

——————

VISION 52 is pleased to republish this interview for its international readers in its own English version, as the content fits well with its own visions, especially those concerning the East Atlantic Flyway with the Wadden Sea as central region:

‘At some point, the Wadden Sea will disappear.’

Karsten Reise, a Wadden Sea researcher from the very beginning, explains in an interview why it is still worthwhile to preserve this natural treasure for as long as possible and to protect it even better.

14 August 2025

13 minutes

Mr Reise, where can we meet you?

At my house on Sylt. I am lucky enough to live on the mudflat side. I just look out of the window to see whether it is high or low tide. When the water is going out, I often set off to get as far out as possible and enjoy the mudflats all to myself, even in the busiest high season. And when the tide is in, I am also happy because I love swimming.

You were head of the Wadden Sea Station at the Alfred Wegener Institute for many years. Most people associate the AWI with research on the world’s oceans, the Arctic or Antarctica. What can a marine researcher do on Sylt?

A whole lot. Compared to my colleagues who sail the oceans with very sophisticated research equipment, access to the Wadden Sea is much more direct. All I have to do to conduct my research is pick up a fork or just keep my eyes open and observe.

What is the most important scientific discovery you have been able to contribute?

That nature is constantly changing and will always remain in motion. Balance is more our wishful thinking – this concept is foreign to nature on the coast. And we have to learn to deal with these changes in nature – and simply let nature take its course.

‘Let nature be nature’ – that is also the motto of the Schleswig-Holstein Wadden Sea National Park, which is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year. How has the Wadden Sea changed since you began your research in the 1970s?

From a nature conservation perspective, there is no doubt that we have achieved a great success story over the past five decades. Even before the national park was established, efforts to take a different look at the coast began, initiated primarily by our Dutch friends. Today, we can say that a new perspective on the coast has established itself, representing a 180-degree turnaround.

How exactly has the perspective changed?

From the assumption that we had a barren and deceptive shallow sea on our doorstep, with nothing really useful to do except fishing, to the understanding that we are guardians of a very valuable treasure, which is now even a World Heritage Site. It is truly remarkable what a change has taken place within 50 years.

Not the Amazon, but the Wadden Sea. Photo: Thomas Krumenacker

To what do you attribute this?

Some things just have to be ripe for the right moment. The Wadden Sea is not isolated in this world. Before, Rachel Carson had written her book about the silent spring, which alarmed humanity. That was certainly a milestone. But the progress made here would not have been possible if people had not started protecting nature much earlier. The coast had already fallen silent around 1900 – due to intensive hunting of birds and seals and, of course, the widespread practice of removing the eggs of coastal birds that nested on the ground in order to sell them on a large scale. Even back then, this brought many species to the brink of extinction and eventually prompted nature conservation associations to buy up small islands to protect the animals. Over time, this gave rise to ideas for more extensive nature conservation and ultimately led to the establishment of the Wadden Sea National Parks.

The establishment of the national park was not without controversy …

Opposition here on the coast was initially very strong. People didn’t want to be dictated to by others, and it took a good 20 years for the mood to change. This was largely due to the many holidaymakers who come here to enjoy nature. And part of enjoying nature is that at certain times of the year, the sky is full of birds, there is a fluttering sound and the salt marshes are in bloom. Many coastal residents found this rather strange at first. But if you want to earn money from visitors, you can’t have diametrically opposed ideas about the coast. Now the people here are just as aware of their coastal treasures and are proud that there is a national park and a World Heritage Site.

Tourism, which is so often seen as a problem from a nature conservation perspective, was a catalyst for the protection of the Wadden Sea?

Definitely. Of course, there are some missteps. You only have to look at the skyline of Westerland on Sylt to see how it shouldn’t be done. However, some islands have taken this as a cautionary example and have developed very exemplary, nature-friendly tourism. This applies not only to the beach and the mudflats. Valuable protected areas have also been created in the dunes, for example.

You are an advocate of the thesis that nature conservation can only succeed if it is done together with the people who live in these areas …

Yes, absolutely. And that also applies to us scientists and to my own mudflat research, of course.

We have to be able to communicate what we find out, and the results have to be something that the people involved in the area can work with. Today, that means the national park authorities with their rangers and experts, but it also means the nature conservation associations, which highlight the remaining problems that still exist despite the success story of nature conservation.

Forty years after hunting was banned, seals are once again a familiar sight in the Wadden Sea. Photo: Peter Prokosch.

Before we turn to the problems, what do you consider to be the greatest successes for nature conservation in the Wadden Sea to date?

The greatest success is that the large-scale diking of salt marshes and mudflats has been stopped. This complete destruction of the ecosystem continued until the end of the 1980s. Then, the new view of the area as a natural treasure and helper in the climate crisis was a decisive success. And finally, something very tangible and visible to every visitor: the end of hunting birds and seals. Not only have seal populations increased tenfold, but escape distance when humans approach shrunk tenfold. For a national park, it is very important that we can see and experience the animals there and that we can see what nature conservation can achieve. Because we quickly forget what we can lose. Auerochsen lived on this coast until the Middle Ages. They did not disappear because they no longer liked the salt marshes; they were hunted to extinction.

Simply beautiful. The Wadden Sea presents a new face every day. Photo: Thomas Krumenacker.

Bar-tailed godwits migrating in the Wadden Sea. Photo: Thomas Krumenacker.

One of the biggest challenges for the protection of the Wadden Sea today is massive conflicts over its use, for example with fishing. Talks on restricting shrimp fishing have just failed. Is this compatible with the national park concept?

I would also place this issue in the very long-term picture. We have talked about embankments. These are no longer pursued, and the former confrontation between coastal and nature conservation has now given way to tentative cooperation. It has been recognised that the mudflats are a wonderful buffer against storm surges and that the mudflats are also feeding grounds for young fish – and for birds. Recognising that nature helps us was therefore crucial in ending a harmful practice. Now we have to tackle a perhaps even more difficult issue: fishing.

Why is it so difficult to limit fishing to an ecologically acceptable level? After all, we are talking about a national park, an area where, by definition, nature has priority.

Seals and birds in particular have a strong lobby. The situation is different for fish. It looks beautiful when the shrimp-fishing boats hang their nets out to dry or go fishing with lowered outrigger boom. These images have become iconic of the coastal landscape. That’s why we find little support among visitors to the coast when we say that shrimp fishing has to stop because it causes great damage to the mudflats. It’s difficult to get people to agree. We have to face up to this task. We need to make the fragile life down there more visible.

How harmful is shrimp fishing in the Wadden Sea?

When nets drag across the mudflats, a lot of life is destroyed and it takes time to regenerate. But the problem is not as bad as it used to be because shrimp fishing has moved further out to sea. This is good news for the mudflats themselves, but overall, the fishing is still far too intensive. This applies not only to shrimp fishing, but to fishing throughout the North Sea. There is a great need for more protection. While much has changed for the better for seals and birds, this is not the case for fish and shrimp.

Can the national park live up to its ecological promise when 97 per cent of its area is used for fishing?

No, but here too we need to exercise judgement. A solution involving fishing remains very difficult, but the issue must be tackled now; the time is ripe.

These are really very, very tough nuts to crack. It will be crucial that we act in harmony with the other North Sea coastal states in order to find ecologically effective and fair solutions. We can only change fishing for the better if it happens across the whole of the North Sea. We in the Wadden Sea must also do our part, but international regulations are needed.

How much fishing can a national park tolerate? As a scientist, where do you see a reasonable compromise?

At the very least, there should be no fishing in half of the tidal creek systems, known as tidal basins. In my view, that would be a first possible compromise. A Wadden Sea coast completely without fishing is currently

not socially feasible.

Does fishing have a greater impact on the Wadden Sea ecosystem than climate change?

I agree with that statement – at least for now. Fishing clearly decimates fish stocks, while climate change brings about a change in species. Southern species are migrating north and species that feel more comfortable in cold water are moving to other regions.

How problematic are the new species that have migrated as a result of climate change or been introduced by shipping for the Wadden Sea ecosystem?

Let’s take the example of the Pacific oyster. It was brought here to replace the native European oyster, which had been wiped out by overfishing. It can be bred quickly and shipped by train to Munich or Berlin without spoiling. This oyster copes better with warming than many other organisms here on the coast. That is why it has quickly established itself outside of breeding farms. I myself had feared that this would displace the native mussel beds. But things turned out differently. Although the oysters dominate, the structures they form now provide young mussels with a good hiding place from crabs, starfish and birds. We now have a very stable coexistence of oysters and mussels sharing the same habitat.

Is the Wadden Sea a particularly ‘foreign-friendly’ sea?

Yes, because it is relatively species-poor compared to other wadden seas. This is still an after-effect of the ice ages, which had a much greater impact on the North Sea region than on many other coasts. There is still a lot of room for growth. This makes it easier for new species to integrate.

Do you have another example of this?

The American slipper limpet, the American razor clam and, more recently, the Manila clam have all been able to establish themselves here without harming the ‘native species’. This is a clear sign that there is still room for development without the system collapsing.

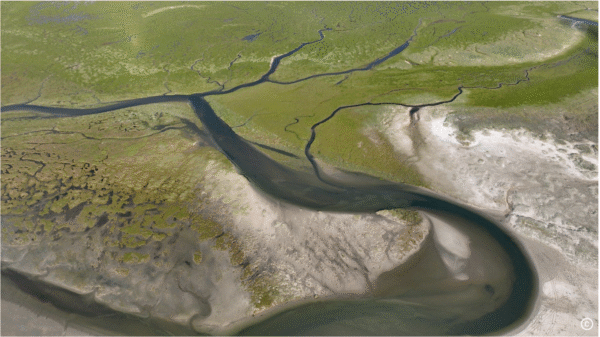

As an ecological system that is already adapted to a great deal of change, the Wadden Sea will probably cope better with the consequences of global warming than, for example, the forests in Central Europe. Rising sea levels, on the other hand, pose an existential threat in the context of climate change.

Is the Wadden Sea in danger of disappearing as sea levels rise?

It will certainly disappear at some point. When that will be is one of the big questions facing researchers. We know that our CO2 emissions have already caused a significant rise in sea levels. We can safely assume that the rise will be in the order of two to four metres. We do not yet know exactly how quickly this will happen, because the change is not linear, especially in Antarctica. If nothing unexpected happens in Greenland or Antarctica, the projection is that the sea level here will rise by about one metre by the end of this century. That is the best information we have at present. And we should plan accordingly.

How can we adapt?

So far, we have been confronting storm surges head-on. When they come, they collide with an almost continuous line of dykes and are thrown back with a great deal of energy. We need to think creatively. And we have now learned that a more flexible coastline is better in the long term. This is because suspended sediment from the sea can no longer reach the hinterland through the dykes, creating a highly dangerous situation: the sea level is rising at the front, while the ground behind the dykes is sinking deeper and deeper. This cannot continue in the long term, and we must now start to try out which solutions are best. It is clear that a lot will have to change.

What could these solutions look like?

We need as smooth a transition as possible between land and sea, and we must redesign the landscape behind the dykes so that water can flow over the dykes or through openings in them without any problems. This landscape already existed on the coast around 1,000 years ago. Back then, people lived on their artificial dwelling mounds in the marshes. We urgently need to move in this direction with the technical capabilities we have today. This would be a proper precondition to allow the sea to bring sediments onto the sinking land.

Climate change is also bringing more heavy rainfall, which will flood a coastal region that lies half a metre or more below sea level. We therefore need to adapt much more than we have done so far. We need a mosaic landscape: there will be areas where intensive agriculture can still take place, but we also need many more areas that can be flooded from time to time.

The system serves to adapt agricultural production to rising water levels. The project is already being exported worldwide.

What will a coastal region of the future look like that has been adapted to climate change in this way?

Of course, there are water buffaloes that cope better with high water levels than dairy cows. In low-lying areas, floating gardens could be created on pontoons, which would not have any irrigation problems. Floating holiday apartments could also provide farmers with an income when it becomes too wet for agriculture. They rise with the tide and sink with the ebb. As a guest, I could then row to the nearest supermarket at high tide. It sounds crazy, but we have to start experimenting. Our Dutch neighbours are already much further ahead in this respect. There are already houses in the low-lying areas that float on pontoons or stand on stilts. In Rotterdam, entire neighbourhoods with floating houses are planned.

Finally, a personal question: What is your favourite animal species in the Wadden Sea?

The lugworm. It doesn’t look very pretty, but it’s incredibly amazing what it can do and how it shapes its habitat so sustainably according to its own needs, creating oxygen reservoirs for many other species in the process. I’m also fascinated by how little we know about this most common and characteristic species of the Wadden Sea – for example, where lugworm babies stay in winter. But I’m on the trail!

We eagerly await the results of this research. Thank you very much for talking to us!