by Peter Prokosch

Norwegian King Harald and Queen Sonja have already arrived at Bear Island on the royal ship ‘Norge’ and will arrive in Longyearbyen on Monday, 16 June. The reason: one hundred years ago, the Svalbard Treaty (originally the Spitsbergen Treaty), came into force, giving Norway sovereignty over the Arctic archipelago near the North Pole. Another reason is that the last Norwegian coal mine (Pit 7) is closing, bringing to an end a long history of mining that has been the main reason for the existence of the Norwegian ‘capital’ Longyearbyen for generations. More than 30 years ago, tourism and research were identified as the two main pillars of future Norwegian activities in Svalbard and have been continuously developed since then.

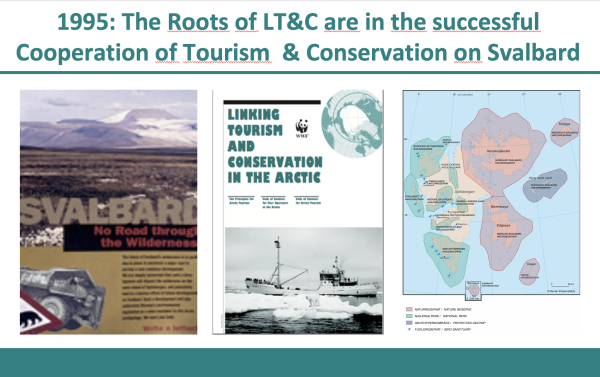

From a nature conservation perspective, there is another important reason that deserves to be highlighted again this year: a campaign launched in 1995 by nature conservation associations and tourism companies against Norway’s misguided plans to build an 80 km road to the Svea coal mine in the south became a unique success story. In a historic session of the Norwegian Parliament (Storting), the arguments of the nature conservation/tourism coalition against the possible first long-distance overland road were not only shared. The road would not only have cut through the largest contiguous green tundra area in Svalbard, ‘Reindalen’, but could also have set a precedent for other members of the Svalbard Treaty (e.g. Russia, which operates its coal mine in neighboring Barentsburg) to build longer roads through the archipelago’s valuable wilderness. Instead, the Storting not only voted against the Svea Road but also called on the government to declare it a national goal to make Svalbard the best-preserved wilderness area in the world. In addition, the ‘green’ tundra areas that were not yet under protection at the time, such as Reindalen, had to be given better protection.

The government complied with the parliament’s request. The road was not built. ‘Svalbard – the best-preserved wilderness in the world’ became a national goal. Several new national parks were created specifically for green areas. Svalbard was given its environmental law. And the Svalbard Environment Fund was established, into which every visitor to the archipelago automatically pays NOK 150 upon arrival.

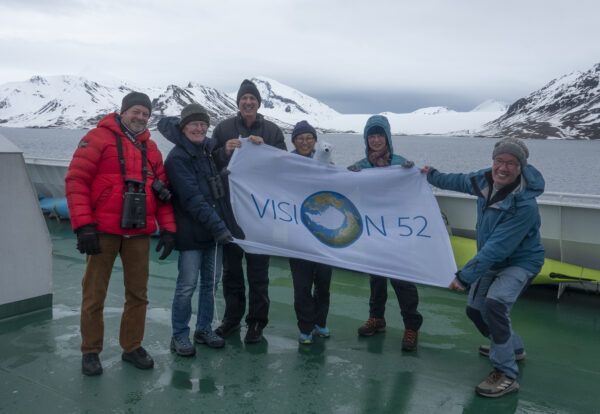

This success story 30 years ago prompted the same tourism companies and nature conservation organizations behind the campaign to continue their joint activities. In workshops in Longyearbyen, 10 principles for tourism throughout the Arctic were developed. They were called ‘WWF Linking Tourism and Conservation in the Arctic‘, translated into various languages of the Arctic countries, and distributed and tested in particular on tourist ships operating in the Arctic. Elements of these principles can still be found today in the guidelines of the Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators (AECO). Svalbard became the first ‘LT&C Example’ of the later-founded NGO ‘Linking Tourism & Conservation’ (LT&C; now ETE-LT&C), which has collected and promoted 53 further examples around the world where tourism supports the creation or further development of national parks and other protected areas.

The current high-level visits to Svalbard and various events serve Norway in particular to declare and consolidate its sovereignty and responsibility over the archipelago. Against the backdrop of the unpredictable interests and policies of the Trump administration in the United States (e.g. towards Greenland) and the speculation about security in the Arctic triggered by Russia’s war in Ukraine, it is important to show prudence and correct misrepresentations of the interpretation of the Svalbard Treaty.

Harp seals on sea ice. Effective marine protected areas in the wider vicinity of Svalbard are needed. Photo: Peter Prokosch

In my opinion, however, Norway should primarily use these anniversaries to further consider how it can continue to pursue and achieve its self-imposed national goal of making Svalbard the best-preserved wilderness in the world. This should include the creation of effective marine protected areas in the wider vicinity of Svalbard, regardless of the outcome of Norway’s current legal dispute with the EU over whether the shelf areas around Svalbard are an extension of the Norwegian continental shelf or are subject to the Svalbard Treaty. In both cases, Norway would have the right and the opportunity to designate marine protected areas with large ‘no-take zones’ and thus also make its own internationally recognized contribution to the 30 x 30 target.

New signpost in Longyearbyen make visitors aware of Norway’s goal to make Svalbard the best-preserved wilderness in then world.

A formally often noted contradiction to Norway’s supposedly progressive environmental policy in Longyearbyen has been the town’s coal-based energy production. This has now been converted to diesel, reportedly as an interim solution. Various solutions are now being discussed, including the establishment of a small nuclear power plant. One would expect Norway to set the highest sustainability and climate-friendly standards for the entire Arctic in Svalbard.

How can the two key players in Svalbard’s future, research and tourism, contribute to the world’s best environmental protection and nature conservation? The King could also ask this question during his current visit and thus indicate the future direction of Norwegian policy on Svalbard. The environmental fund, which is fed by more than 100,000 visitors annually, should also offer incentives for optimal solutions. Thirty years ago, tourism and nature conservation already set a positive example. Now new, strong, and convincing initiatives are needed.